Sale on canvas prints! Use code ABCXYZ at checkout for a special discount!

There was just one more location we wanted to explore before heading home after one of our Death Valley adventures. It was February, and Stephen and I had hiked Surprise Canyon to the ghost town of Panamint City. It was a five-mile uphill hike to this former silver mining town that boasted a population of 2,000 people prior to being destroyed by a flashflood in 1876. Surprise Canyon, named for the perennial spring and accompanying stream, was a tough hike. We named the first stretch “the jungle” because it was completely overgrown with lush, green, overhead vegetation. A machete would have come in handy here. Then it was rock, rock, rock and more rock as we made our way up the canyon. Somewhere in this section one rock was carved with these words; HUMAN STUPIDITY HAS NO LIMITS 1997. Nearing the end of the trail a towering brick chimney, used in the smelting process, stands witness to this notorious town that once hosted a dozen saloons. The sun had set and it was dark when we arrived back in camp at the end of the day.

Skidoo, another long-forgotten mining town, was our final stop on this Death Valley adventure. Infamously remembered as the town that hung the same man twice, the drive to Skidoo is a long winding dusty, unpaved trail out to what feels like the middle of nowhere. At the turn of the century, a 23-mile long steel pipeline had been laid to quench the thirst of the Skidoo mill that only produced a few million dollars in gold. Talk about unlimited human stupidity! In 1917 the whole pipeline was scrapped and sold to help the war effort. Ominous dark clouds filled the sky when we finally arrived at the Skidoo ruins. We hiked around the remains of the enormous old timber constructed mill with all of its rusted iron fittings, taking pictures and realizing that the temperature was dropping rapidly, and yes, those were snowflakes falling from the sky. The metal legs of my tripod had grown so cold that I could barely hang on to them and we were convinced that we had each begun to turn blue with cold. Returning to the cab of the pickup to escape the cold, my final comment to Stephen about Skidoo was “I’m freezing in Death Valley!”

Death Valley called my name for many years before I ever had the opportunity to visit this land of relentless heat and the blinding white salt flat that marks the lowest spot in North America. Since then, numerous trips to this legendary Valley and surrounding region have been unforgettable.

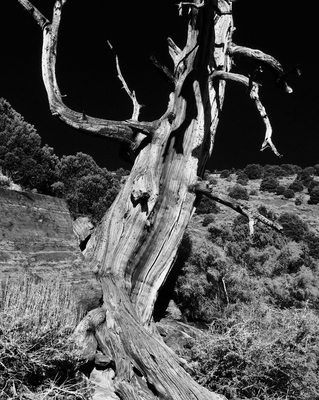

Most people don’t think of altitude and evergreens when the topic of Death Valley is mentioned, but one of my most distinct memories is from the summit of Telescope Peak, 11,000 feet above the “sink” as the Badwater Basin far below is sometimes referred to. David and I had camped at Mahogany Flat campground overnight, planning on an all day hike the next day to reach the summit of Telescope Peak. From an elevation of 8,200 feet, the trail begins on the east side of the mountain with the trail head sign reading seven miles to the summit. So, our hike began on a clear, sunny September morning. Countless little black lizards were sunning themselves in the morning heat on the east side of the mountain that morning, and along the way we stopped numerous times to take in the incredible views into the depths of the Valley below. About midway into the trail we came to a wide saddle that provided a view of the Panamint Valley to the west. It too, lay thousands of vertical feet below us. Between us and the bottom of this valley there were enormous steep walled canyons, bottomless in appearance. Continuing along, we began passing trees. One old severely weathered, lifeless tree stood like a ghost sentinel along the trail. There were countless pieces of black rock layered, black, tan, black, tan . . . ; they looked like the pages of old books. Further along there were more trees, living trees; short squat tough looking little evergreens that had that look about them that says we’ve stood the test of time and the elements. Clouds began appearing overhead and their shadows created a fascinating pattern on the barren mountainside. At last the summit was visible. Breathing was difficult in the thin air. David arrived at the summit ahead of me, no surprise; he’s a marathon runner. I’d only been standing at the summit for a few moments when it happened. Out of nowhere a bird, a bird of prey with wings tucked, flashed by us on a steep power dive into one of the canyons below. Far, far below some poor rabbit or squirrel was about to become lunch for a hungry bird. It was an incredible sight! Unforgettable!

When the conditions are right, the clarity of the desert sky is unbelievable. Distances are very difficult to determine because of this. A mountain or sand dune that appears to be just a few miles away, can in reality be twenty-five or thirty miles away. This sense of optical illusion is ever-present wherever one travels in this area. I love the way Mary Austin described this wonderful desert phenomenon “For one thing there is the divinest, cleanest air to be breathed anywhere in God’s world.” Death Valley is the lowest place on the continent, and in this land of extremes one can also see the highest mountain peak in the lower 48, Mount Whitney, 70 miles distant. One October day I hiked to the top of Wild Rose Peak at an elevation of just over 9,000 feet. Conditions that day were perfect, cool temperatures in the shade, comfortably warm in the sun, and there was a waning halfmoon low in the morning sky. There wasn’t even the tiniest breath of wind or a cloud in the deep blue sky overhead when I reached the summit. Glaring white salt, snow-like in appearance shimmered from the Badwater Basin 9,000 feet below me to the east. Ridge after succeeding ridge, in ever lighter shades of grey spread west from where I stood, and there in the distance 70 miles away was the eastern crest of the Sierra Nevada mountains. The light colored, granite face of Mount Whitney piercing the sky higher than anything else in sight. It seemed close enough to reach and touch! Unforgettable!

Time spent in Death Valley is time spent in an everchanging kaleidoscope of geologic color unlike anything else I’ve ever experienced. Walking through Golden Canyon late in the afternoon one Spring I saw yellows, oranges and golds of a dozen shades painting the pigmented hills and badlands. Deeper into the canyon, the Red Cathedral, a massive and intricately eroded cliff surged up into view. A rich reddish-brown run along the apex of the cliff line, interrupted by deep erosion scars. Candy cane stripes of golden yellow and cinnamon brown blanket the badlands below. From the top of Golden Canyon the Zabriskie Point badlands come into view. At least a half dozen shades of brown ranging from dark chocolate to milkshake brown decorate the landscape. In the morning the Manly Beacon peak stands out in a half dozen shades of yellow earth, banana, daffodil, and butter against the distant purple tone of the Panamint Mountains. Wait a couple of hours and all of these colors will have taken on a new look as the sun makes its trek across the desert sky, and at evening the colors appear to glow. Along the four mile long Artist’s Drive is one of the most concentrated areas of geologic color in the Valley. This eye-dazzling oasis of color is appropriately named the Artist’s Palette. A road side interpretive sign describes things like this “Various mineral pigments have colored these volcanic deposits. Iron salts produce the reds, pinks and yellows. Decomposing mica causes the green. Manganese supplies the purple . . . I’ve seen dozens of onlooking tourists stand amazed before this rainbow of rock, and with changes in the angle of sunlight throughout the day the colors take on new nuances of color. Strangely enough just minutes before viewing this wonder I stopped along the road to get a picture of another desert curiosity, only this one was nearly colorless. It was a single plant, a small burro weed growing in an expanse of loose, gravel sized lifeless rock. The leaves of this plant grow at an angle decreasing direct sun exposure and they are pale gray, nearly white in color. I could go on and on about this wonderland of color etched in my memory, but my time and space are limited, unlike the colors I’ve attempted with inadequate words to describe.

It’s the last week of December and I’m thinking about the new year ahead. I haven’t returned to Death Valley in more than a year, and the Valley is calling my name again. I’m hoping to return in the next few months, camera in hand. As Mary Austin put it “None other than this long brown land lays such a hold on the affections. The rainbow hills, the tender bluish mists, the luminous radiance of the spring, have a lotus charm.”